This article was originally circulated as HVM Society Snippets – No.281 on 5th June 2021.

“I, James Blunt”, first published on March 26th, 1942, is HV Morton’s one and only work of fiction. As we have discovered in previous posts this novella was written as part of a propaganda exercise to stiffen resolve on the home-front during the Second World War. It was published initially in Britain as a soft cover edition and later in North America, Australia and New-Zealand in hard-covers. It was also adapted for radio and broadcast on the BBC Home Service on 26 June 1942 at 8.20 p.m..

Morton refused any form of payment for the book, and was personally thanked in writing by British Prime Minister Winston Churchill for his contribution to the war effort. In his letter to Morton of 20th August 1942 Churchill compliments the author on the wide circulation of his work and tells him it is “an excellent thing that the horrors of a Nazi occupation should be brought home to the British people in this way”.

The book takes the form of a diary which opens in September 11th 1944 in a fictitious Britain five months after what the eponymous Mr Blunt, a veteran of the last conflict, refers to as “The Capitulation”, namely the defeat and occupation of Britain by the forces of Nazi Germany.

Blunt tells us of a changed Britain – dark and grim – of spies and informers, where petty criminals and bureaucrats have been elevated to positions of power, newly opened German State Schools teach British children to speak German, the Swastika hangs over Buckingham Palace and America is “the last obstacle to the World Order”. In short, Britain is enslaved. Blunt is in constant fear of his life and fears for the safety of his daughter and his outspoken sister under the new regime.

It is a well written work. Morton emulates the diary style of the ordinary man, employing contractions and slang phrases which he wouldn’t dream of using in a serious context elsewhere; he also makes liberal and uncharacteristic use of the exclamation mark. Morton is meticulous when describing Nazi institutions and the uniforms and ranks of the occupying forces; local affairs are governed by a Gauleiter, national issues by a London-based Statthalter whose portrait hangs in every public building. Morton, as always, has done his research.

“I, James Blunt” is part of a body of fiction known as alternative history. As a science-fiction as well as a Morton fan I have long had a keen interest in this genre.

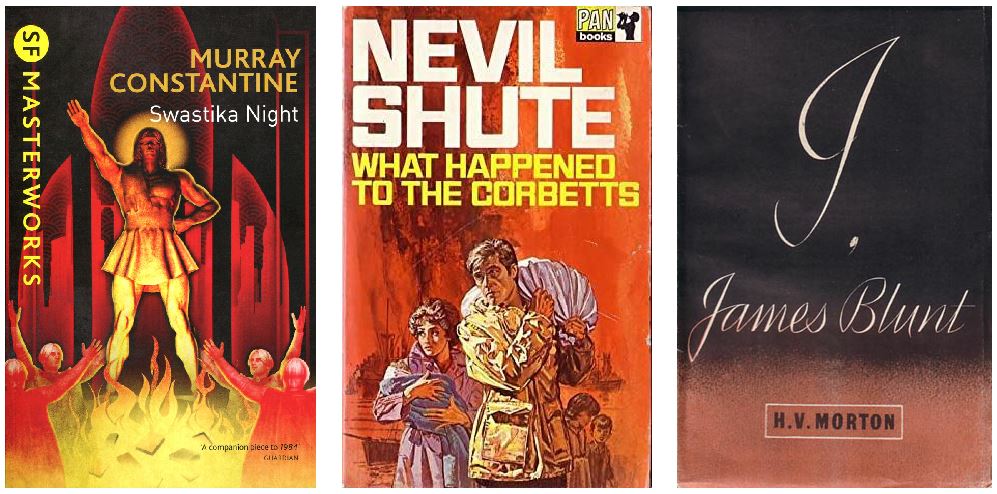

A favourite topic of alternative history books is the fictional scenario where the Nazis under Hitler have won World War II. Some, including Morton’s offering, were written before or during the war. Of this sort one of the most visionary is “Swastika Night”, by feminist author Katharine Burdekin under the pen-name of Murray Constantine. This was written in 1937 but accurately predicted the rise of the Nazi Party in Germany, the doctrine of the master race, the subjugation of women and the quest for world domination leading to global conflict.

The majority of such books relating to World War II though, were written after the war presenting what-if theories about a fictional world where the Axis powers had defeated the Allies instead of the other way around as actually happened. There are countless examples of this kind, there is even a wikipedia page dedicated to them and a book on the subject: “The World Hitler Never Made” by Gavriel D. Rosenfield.

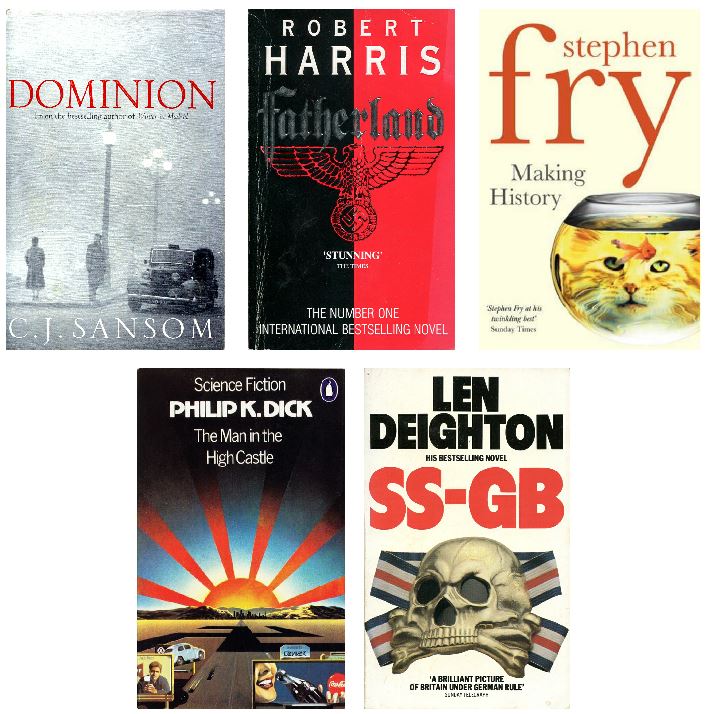

Some of my favourites include “Dominion”, by CJ Sansom, “Making History” by Stephen Fry, “The Man in the High Castle” by Philip K Dick, “Fatherland” by Robert Harris and “SS-GB” by Len Deighton. The last three have been dramatised for film or television.

Len Deighton’s “SS-GB” is one of the best. As with “I, James Blunt”, there is great attention to detail in his descriptions of Nazi hierarchy and institutions and how they might have been applied in a defeated Great Britain.

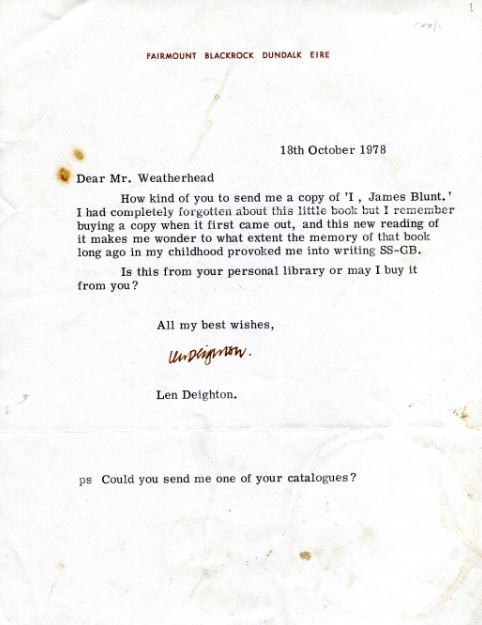

It’s not often that things come together as neatly as they did for me a few months ago when I discovered two letters for sale on an internet auction site. They were both from the author Len Deighton to a book-seller by the name of Mr Weatherhead, the first asking if he had in stock a map of 1930’s Germany and the second (which gave me great satisfaction to read), from 1978, thanking the seller for sending him a copy of “I, James Blunt” and suggesting Morton’s “little book” had an influence on his decision to write his own novel “SS-GB”. That’s quite a feather in Morton’s cap if you ask me!

You’ll notice Deighton is keen to buy the copy of Morton’s novella – he obviously had a collector’s eye, it’s one of the rarest titles in his oeuvre.