A comparison of the interwar travelogues of J.B. Priestley and H.V. Morton

Introduction:

What follows is a comparison of the accounts of different journeys around England, namely J. B. Priestley’s 1934 English Journey and H. V. Morton’s two “England” books, In Search of England (1927) and The Call of England (1928).

H. V. Morton compiled his books from a series of articles he had written for the Daily Express newspaper between 1926 and 1928 of his impressions as he travelled around England in a small motor car. Each book is presented by and large as if it were one continuous journey. Morton’s declared intent was to encourage “an understanding love for the villages and country towns of England” in order to better preserve them for the future, although he admits concerns that this must be balanced against the “vulgarisation” of the countryside (iSoE p. viii). The books are light-hearted travelogues and generally politically neutral . Although suggestions of Morton’s personal views are apparent in the introductions, at no point do they intrude on the relaxed, amiable style of his narrator in the main text.

Priestley’s book was commissioned by his publisher, Gollancz and was an account of a journey which he conducted around England in late 1933, initially by motor coach but later by car and the occasional tram. Describing his mission, Priestley states “I am here, in a time of stress, to look at the face of England, however blank or bleak that face may chance to appear and to report truthfully what I see there” (EJ p. 61-62). As such, much of the book is overtly political and, rather than the reserved tones of Morton’s narrator, the reader experiences Priestley’s strongly held, personal views on much of what he encounters during his travels as he declares he is “here to tell the truth and not make up a Merrie England” (EJ p. 119). As journalist and author Andrew Marr puts it “Priestley wanted to rub the noses of Southern middle-class Britain in the reality of the other nation” (Marr, 2007, p. xxii).

Different Worlds:

As might be imagined, despite containing a few intriguing similarities, the two works are very different. This exercise is more though than simply a comparison of two authors, it is also a comparison of two Englands. The world of Morton’s ‘England’ books lacked things which would have been familiar to Priestley only eight years later, from Heinz Beans to Penicillin, from the Times crossword to equal suffrage, but what separated their two worlds so utterly and the reason such a comparison can never be entirely fair, was the devastation of the great depression of 1929. The Wall Street crash knocked the economic heart out of Britain’s industrial centres almost at a stroke, decimating production, ruining export markets and laying men off in their hundreds of thousands.

Morton’s essays were written in the twenties, before the crash, at a time when war-time restrictions were being lifted and when Britain was beginning to look forward to a prosperous future. They betray an airy optimism which is absent from Priestley’s account, written as it was at the height of the depression, by which time the world of Morton’s gently spoken narrator, with its bosky dells and winding village lanes had changed irrevocably. The statistics which Priestley himself employs in English Journey speak for themselves about the state of the economy of the time. In 1920 Britain was producing nearly 2 million tons of shipping but by the time Priestley came to write his travelogue that had been reduced by a brutal 90% to less than 2 hundred thousand tons (EJ p. 343). This led to massive hardship, not just in the ship building industry but in related industries too, mainly steel and coal production. Consequently the industrial towns and cities visited by Priestley were in an appalling state with unemployment reaching as high as 70% in places. This inevitably caused profound social changes and Priestley’s account of a Blackshirts’ rally, with its communist hecklers in Bristol is symbolic of the polarization of Britain and the rest of Europe along extremist political lines (EJ p. 29).

Morton of course would have been blissfully unaware of this impending disaster as he steered his slow and careful way around the highways and byways of England and this must be borne in mind when making a comparison. To be fair, following the depression Morton was fully aware of how the country had changed; when he was asked, in 1933, to reissue a book originally written in 1926 (A London Year) Morton was reluctant, pointing out that the first edition was “written during that brief waltz of wealth after the War” and expressing concern that a reissue might appear “quite out of touch with our times” (Morton, 2004).

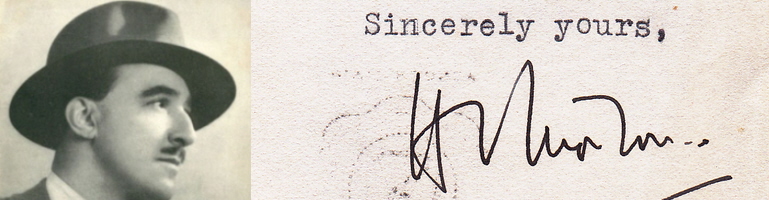

Different Men:

Not every difference between the two works can be attributed simply to the times in which they were written of course. The difference between the authors themselves and how each one deals with the subjects of industry, wealth and social conditions is still an important factor. While life at the time of the writing of English Journey offered plenty of grist to the mill for the social commentator, Morton’s 1920’s England wasn’t entirely without its share of industrial unrest too. One has to look closely though to decipher where he has referred to arguably the most significant industrial relations event of the decade, the national strike of 1926. According to biographer Michael Bartholomew (2004, p. 95) the only mention it received in Morton’s work was a reference to the miners of Lancashire squatting on their haunches “like Arabs“. There is no hint that these disconsolate men are on strike and within a few lines Morton has breezed on and is sharing a joke with the reader about Wigan pier. It is hard to imagine Priestley being so cavalier if he had been writing about the same subject.

Apart from the different agendas of the two authors the general tone, the literary style, of the two is poles apart. Priestley is determined to reject any hint of sentimentality, he even accuses Dickens of being a “sentimental caricaturist” (EJ p. 274) and despises what he refers to as the creators of ‘Merrie England’, “who brood and dream over… almost heartbreaking pieces of natural or architectural loveliness at the expense of a lot of poor devils toiling in the mud” (EJ pp. 398 and 119). Priestley’s views are opinionated, thought provoking and challenging. He is the stern moralist who knows what is best for the people and isn’t afraid to proclaim it, the voice of the reformer, the social engineer, the ‘man with the plan’.

When it comes to the prevailing social conditions of the day, be it describing the base brutality of a Newcastle boxing ring, the deplorable conditions in the slums of Stockton on Tees or the unremitting, bleak despair of Tyneside, Priestley is at his finest. He pulls no punches as he ruthlessly exposes the full horror of the conditions which exist in mine, mill and shipyard within just a few hours of the capital. At a stroke he vapourises any convenient illusions about the working man which the wealthy classes of London and elsewhere might chose to maintain for their own peace of mind. Priestley is in search of the truth, he has no truck with peace of mind.

Morton on the other hand has a relaxed, languid style. He speaks with lyrical, almost poetic tones. He will seek out individuals and allow his story to be told through them and their experiences. His prose is intimate and personal, the reader feels as if they are being taken into Morton’s confidence as his narrative unfolds. As early as page one of The Call of England he is excitedly whispering to the reader about the joy he feels at the new adventure which lies ahead. His is the voice of the little person, he is the everyman; not the reformer, but the one who will be reformed. He is not blind to the hardships of the industrial cities, at one point comparing the recruitment of casual labour in the docks of Liverpool to a slave market, but by and large his aim is to entertain and tantalise the reader, not to dwell on uncomfortable topics. Morton is as anxious to please as Priestley is to confront.

This is not however, simply a case of one author nobly championing the working classes, while the other flits, magpie like (iSoE p. vii), from one glittering Arcadian jewel to another. In Morton’s writing he attempts at all times to be fair to his subjects and, by and large, if he can find nothing good to say about something then he will say nothing. While this means, at times, we find him glossing over some unpalatable truths it does mean that Morton’s style is more generous while Priestley sometimes accounts less well for himself, on occasion coming across as somewhat carping. He seems to find it difficult to give credit where credit is due, even when the subject is undeserving of his wrath. Consider for instance the two authors’ accounts of England’s second city, Birmingham.

Priestley described himself as a “grumbler” with a “Saurian eye” (Gray, 2000, p. 42) and perhaps this accounts for some of his remarks as he alternates between patronising and criticising Birmingham. Having initially hoped that the entire city (which he describes as “a dirty muddle“) had been “pulled down and carted away” (EJ p. 78) he takes a tour of the Corporation Art Gallery and Museum, courtesy of its director who is keen for Priestley to see the work of local craftsmen. In a few short paragraphs Priestley damns the work of aspiring young talent with extremely faint praise, describing them as “surprisingly good” and condemns locally designed silverware out of hand as “tasteless” although “admirably executed” following which he turns his back on the natives and proceeds to sing the praises of international painters for nearly two pages.

Morton, on the other hand, anxious perhaps to make amends for having ignored Birmingham in his first book, addresses the balance in the second by initially taking issue with a gloomy assessment of it (a “rotten hole“) from an inebriated commercial traveller on a train (both books make liberal use of the unfortunate commercial traveller as a foil in order to make many a point). He then goes on to announce his arrival at New Street station (having abandoned his car for once) with a light hearted paragraph on the city’s many achievements (“the city whose buttons hold up the trousers of the world“) before going on to praise its smartly turned out policemen and the classical columns of its town hall. Morton isn’t unaware of the less inspiring aspects of the city – its “drab uniformity” and “outer crust of ugliness“, but this is countered by reference to great camps of industry and praise for Birmingham’s successful commerce and the vigour and drive of its hard working people (CoE p. 175-179). Morton has an eye for the colour and vibrancy of the city which, even given the different times, seems to have escaped Priestley.

Both authors contrive to visit chocolate factories on their travels but while Morton (in York) is marvelling at the manufacturing process, expressing an interest in the colourful little hats and coats in the cloakroom and patronising his guide by complementing her on having a “pretty head full of statistics“, Priestley is agonising over whether the Cadbury plant at Bournville, which he acknowledges is providing its workers with some of the best conditions in the world, isn’t too paternalistic and, by offering its employees generous benefits both in and out of work, isn’t bringing about the beginning of the end of democracy. Priestley finally ends up apologising to Cadbury’s for his gloomy introspections at their expense!

Neither author appears entirely at ease in a crowd of strangers although here too they deal very differently with the subject. In Morton’s case in the crowded Manchester Royal Exchange (CoE p. 131) he positions himself in the strangers’ gallery high above the crowd (which he describes briefly as ‘the monster’) from where he picks out and follows a single individual as he weaves through the throng, in order to enlighten the reader – a cheerful little man who rubs his chin and makes a joke and who the narrator hopes is kind to his wife. Priestley by contrast has no time for such whimsical niceties and when visiting the crowds at Nottingham’s goose fair he appears striding, raptor-like through the multitude, his keen eye sparkling with disapproval. Priestley pulls no punches as he describes the scene of Wellsian horror around him with the unfortunate citizens of Nottingham reduced to “human geese“, the boys consigned to a “sub-human race” and the girls condemned as “slavering maenads“. Paradoxically, one of the few points in the book where Priestley appears happy is with a crowd of his peers at his regimental reunion, which he describes as a mass of “roaring masculinity“.

In other sections there are a few fascinating similarities to be found. Sweeping statements for instance are perhaps inevitable when undertaking the task of cataloguing an entire country but Morton’s description of Birmingham in his first book as “that monster” and Priestley’s description of Swindon as a “town for dingy dolls” built by social insects (EJ p. 38) probably did little to endear either author with their respective local readerships. Both being seasoned writers, they could turn their pens to a pithy, evocative phrase – Priestley describes the day he arrives at Southampton as being “as crisp as a good biscuit” (EJ pp. 12-13) and he portrays a budgerigar wonderfully as “flashing” about a room “like a handful of June sky” (EJ p. 127). Morton dreamily describes the distant ridges of the Yorkshire moors as being “as blue as hot house grapes” (CoE p. 88) while the ruined Abbey of Fountains is “like an old saint kneeling in a meadow” (CoE p. 68) and the road he comes to Manchester on is “as hard as the heart of a rich relation” (CoE p. 68). By contrast, as men of their age, both authors were capable of remarks which are jaw droppingly inappropriate to the modern ear – Morton merrily describes London as having “as many moods as a woman” (iSoE p. 51) and Priestley at one point opines to the horrified reader that he dislikes the ‘blues’ being sung in Blackpool as they concern the “woes of distant Negroes, probably reduced to such misery by too much gin or cocaine” (EJ p. 268).

Conclusion:

In the final conclusion the difference between the works is the difference between poetry and prose, documentary and drama; Priestley is Britten’s ‘Peter Grimes‘ while Morton is Eric Coates’s ‘Fresh Morning‘. Priestley’s work is powerful and intended to shock, Morton’s is gentle and intended to entertain; both are meant to inform. Each vividly captures the prevailing mood of their times, one looking back from a period of prosperity to a peaceful, halcyon England as it was before the carnage of the Great War, the other struggling to come to terms with the grim realities of the modern world in a time of great hardship. Priestley certainly gave the people what they needed to hear but Morton perhaps gave them what they wanted to hear.

Both men had a deep love for their country, despite having different stories to tell, and both would probably have been happy to have been described, as Priestley describes himself in his closing chapter, as ‘Little Englanders’. Both give a rounded view of England, despite their declared prejudices, with Priestley, while claiming to despise ‘Merrie England‘ and its creators never the less finding his own version of Arcadia walking with friends on his beloved Yorkshire moors (while managing to stay in character by sniping at unsuspecting cyclists). Morton too, despite initially devoting a mere seven paragraphs in In Search of England to what he described as the “monster” towns and cities of the North where the only good thing he has to say about them is that, compared with the surrounding greenery, they aren’t that big, by the time he comes to compile The Call of England a year later, has come to respect the power and productivity, vigour and vitality of England’s industrial heartland.

Finally:

Priestley’s English Journey is credited with influencing George Orwell’s 1937 work, the definitive Road to Wigan Pier, itself a no holds barred account of despair in the industrial towns of England. What influenced Priestley in his work is interesting to speculate. Almost certainly he would have known of and probably read Morton’s ‘England’ books, they were among the most popular books of their genre at the time, and this may well account for some of his antipathy to ‘Merrie England’ – Morton certainly does his fair share of the brooding and dreaming over “architectural and natural loveliness” which Priestley so detests. There was also another, less well known work however, published by the Labour Party the year before English Journey, to which Priestley might well have had access while preparing his work and which could conceivably have had some influence. It too is a frank and disturbing account of life in six English industrial cities at the height of the great depression. Its author also expresses outrage at the condition of the slums which he visits and castigates landlords for their role in creating such horrors. He argues passionately for state intervention to alleviate the suffering which he so vividly depicts. In tone and spirit it is not that far removed from Priestley’s English Journey. Its title is What I Saw in the Slums; the author is H. V. Morton and ‘Merrie England‘ is nowhere to be seen.

References:

Bartholomew, M., (2004) In Search of H.V. Morton, London, Methuen

Gray, D., (2000) J.B. Priestley (Sutton pocket biographies), Stroud, Sutton publishing

Marr, A., (2007) A History of Modern Britain, (paperback edn., 2008), London, Pan Macmillan

Morton, H.V., (1927) In Search of England, (2nd edn., 1927) London, Methuen

Morton, H.V., (1928) The Call of England, (14th edn., 1941) London, Methuen

Morton, H.V., (2004) in Devenish, P., Ann’s done it again!: HV Morton Society Collectors’ Note No.5 [online]

Priestley, J.B., (1934) English Journey London, Heinmann, Gollancz

This article originally appeared in the Albion Magazine Online.