One of my favourite of Morton’s works is his “I Saw Two Englands”. Originally published in 1943 this was a record of the Two Englands witnessed by Morton on his travels around the country before and after the start of World War II.

Setting out on 15th May 1939, at a time when, according to Morton, “… the laurel wreath [Prime Minister] Chamberlain had worn since Munich was becoming rather shabby” and it was widely recognised armed conflict with Germany was inevitable, Morton devotes the first half of his book to an account of a nation on the eve of war. The second half is set after the start of hostilities, beginning on October 17th of the same year and continues the tour, with the country still presided over by its ineffectual leader as the war machine gathered pace and an incredulous England was beginning to unite in the face of adversity.

Morton describes the grim, calm determination of a nation which has been brought to the brink but isn’t yet sure of what to expect. His closing paragraph summarises the prevailing mood during the so-called ‘phoney war’, as he finally sets out for home at the end of November:

“So upon a winter’s day I returned from my journey through war-time England, vaguely disturbed by the apathy of a nation that lacked a leader, a nation that was not even half at war, a nation sound as a bell, loyal and determined, war-like but not military, a nation waiting, almost pathetically, for something — anything — to happen“.

This appraisal is followed by a postscript written twelve months after the start of his journey which describes how things have indeed begun to happen, with a vengance. Dunkirk, the blitz, the Battle of Britain have all galvanised the nation to action and life on the home front has changed almost, but not quite, beyond recognition. Morton describes English villages reverting to their war-like pasts, as in mediaeval or even Anglo-Saxon times, “… ordinary men have run to arms in order to defend their homes“. This included Morton himself who in the final pages stands watch from the church tower in Binstead village where he commands a Home Guard unit.

War, says Morton, “… has brought us face to face with the fact that we love our country well enough to die for her“.

Some time ago a fellow member of the HV Morton Society drew my attention to a special edition of “I Saw Two Englands”. This was published, twenty-seven years ago now, to mark the 50th anniversary of the outbreak of World War II and is presented in a lavish, full colour, large format volume. The work has been revisited and photographed by Tommy Candler, and it was suggested that as the original book purports to show how England was just before the War in case it changed utterly and also to portray it in a state of readiness for war, the photographs add a valuable extra dimension by showing how it is has managed to stay the same.

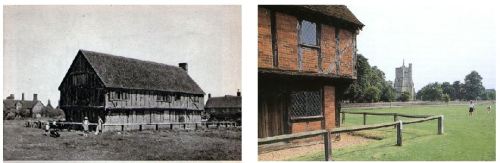

John Bunyan’s Barn, near Bedford, photographed by Morton (left) and Candler (right)

John Bunyan’s Barn, near Bedford, photographed by Morton (left) and Candler (right)

“I saw the Moot Hall on the village green where Bunyan danced so sinfully”

Candler is a superb photographer and her compositions illustrate Morton’s prose perfectly. Through her eyes we are treated to a contemporary view of much of what, half a century before, HVM had described and had been illustrated by the photographs in the original, allowing the reader to compare then with now.

The crookmaker of Pyecombe photographed by HV Morton.

The crookmaker of Pyecombe photographed by HV Morton.

His art now employed for decorative purposes in the later photograph by Candler.

Candler also selects archive pictures for the later sections and we become privy to scenes which would not have been permitted in the original but were detailed in the text as Morton portrayed a nation gearing up for defence. A tank factory, groups of German POW’s (according to Morton they were, despite having launched torpedoes against our ships, “average looking fellows”) and a flight of Wellington bombers (likened by HVM during their construction to living creatures with veins and arteries of red, white, yellow and green cables) making a banking turn over rural England are all brought to life, adding extra an extra depth.

A tank factory somewhere in England.

A tank factory somewhere in England.

“Bending over their machines the men might have been pupils in some gigantic technical school”

The 1989 edition of “I Saw Two Englands” is readily available second-hand at heart-breakingly modest cost and is well worth keeping an eye out for. It would make a handsome edition to any collection of Mortoniana and is of course, well on the way to becoming an historical arefact itself!

For further reading there is a contemporary review entitled In Search of the Real England by R. Ellis Roberts in The Saturday Review of May 1st, 1943. Another review can be found on the worthwhile books blog whose motto is “Keep calm and read classics“.

With best wishes,

Niall Taylor, Glastonbury, Somerset, England

This article was originally distributed on 9 January 2016 as: HVM Society Snippets – No.196.